News

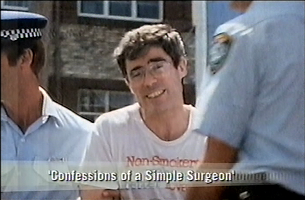

Arthur Chesterfield-Evans

Confessions of a simple surgeon

Q: How did you get started - who influenced you?

About 1980. I heard of BUGA UP but contact was via NSMA. I was more influenced by Freddie Cole than Peter, as Fred was very quick to claim his work and Peter never said a word. In retrospect this was a huge problem as it led to my biggest mistake in politics, when I got Freddie to speak on BUGA UP at the Young Liberals' Conference and Premier Nick Greiner was there. Greiner and I were to clash later at the following year's Young Liberal Conference in Melbourne when I was trying to get a ban on tobacco ads as part of Young Liberal policy. Greiner and Kennett were in an anteroom, and I tacked them both at once on the issue. Kennett was a foul mouthed man by any standards and had been involved with advertising; I think even with tobacco and told me to go in no uncertain terms. Greiner's opinion that anti-tobacco people were all crazies. The harm he has done by his influence on Liberal policies both before and after his Premiership is huge. One Liberal told me when I was in Parliament a decade later that the Liberals 'would not do anything (on tobacco) that Nick did not like'.

Q: Who did you recruit or encourage?

I took the concept to the 5th World Conference on Tobacco and Health in Winnipeg Canada in May 1983. BUGA UP was the hit of the conference and is the only paper I know that had to be given again because the people could not fit in the room. We became famous at that conference as the most radical group in the world and were motioned in the Tobacco Industry's assessment of that conference as a turning point when the radicals, Gray and Daube got control of the anti-tobacco movement. The fact that we were not criticised but praised by the other health groups was regarded as highly significant by the tobacco industry - as we found later through leaked documents. It might also be noted that at that conference there was no activist meeting scheduled On the Thursday night Stanton Glantz convened such a meeting and Jeanne Weigum of Minnesota became the information exchange person for tobacco control in the world, sending big envelopes of stuff to everyone on the list from the conference. BUGA UP went in those packages for some time also.

Q: What was your main motivation?

I was horrified by the harm tobacco caused and that the advertisers were so amoral in pushing whatever they were paid to push. They took no responsibility for the consequences of the promotions.

Q: When did you first get involved/paint a billboard?

Probably around 1982 or 83

Q: Which type/location billboards did you target?

Ones that I could reach without an extension, so mainly railways and shops, also bus stop shelter sheds. I focussed specifically on tobacco billboards using spray cans.

I worked mostly alone on the way home from my radio doctor work, but a couple of times with others.

Q: What non-billboard activities did you initiate or participate in?

Q: What non-billboard activities did you initiate or participate in?

Quite a bit of street theatre: A BMW & tobacco promotion at Centrepoint where others wore a skeleton suit. Demonstrations, including some I did alone in a tutu at the Opera House and the Australian Ballet Xmas party in my Benson and Hedges tutu with my then girlfriend dressed as an undertaker with a dollar sign in her top hat. We paraded in the competition for best costume. The wings of the arms of the gold lame suit said, 'Smokers are dying to bring you the ballet'. We didn't win.

Q: When did you stop or wind down, why?

After we did the public billboard refacing outside the Sydney Sports Ground at 11am on a Saturday before the 1983 Rugby League Final for Stephen Rose's BBC QED programme, I figured (quite wrongly) that it was just a matter of time as we had 'won'. The sponsorship of Formula 1 finally finished in 2006, a mere 23 years later!

Q: What do you think was the main effect of your/BUGA-UP's activities.

BUGA UP redefined the tobacco debate. It formed the extreme pole of anti-tobacco action, and so made all legal activities moderate by comparison. It also redefined the debate as a renegade industry killing people as the driving force, rather than a personal choice. Not as smokers v non-smokers as the industry had portrayed the debate prior to this time. It also took the problem from the medical profession and kicked it into the political arena. In the public mind, the moral contrast of the good guys going to gaol and the bad guys having the police enforce their 'right to lie' made it a political problem like never before.

The effect on advertising was more subtle and ultimately lost as the 'self regulation' system remained a farce and was abolished as soon as the heat went off it. But advertisers probably dumped tobacco to save their own skins. Buga Up was the wedge between tobacco and the advertising companies, which became concerned for their own fates.

A US group, the Badvertsing industry and another satiric group came along after us, deconstructing ads, though I am unsure if they ever conceded that they followed us. Two Swedish Health bureaucrats took our Ad-Expo stuff and produced very high quality material at government expense called 'Smart Promotion' The health dept in Sweden was sued by Swedish tobacco company and R.J. Reynolds went for copyright violation because a blond Camel man was on the cover. It was republished the same except for a brown cover (which made the previous ones collectors' items) and a disclaimer which translated graffiti as 'scribble' which made absurd reading and told children that they must not do it. The publicity made tobacco look very silly. This made a big splash in Sweden and influenced their government, then they came to Australia and I got the NSW Cancer Council to say that they sponsored them. (They paid for a morning tea and chaired the press conference) The object was to show that even national governments agreed with BUGA UP).

Wikipedia

Wikipedia Youtube - BUGA-UP, recalling their campaign.

Youtube - BUGA-UP, recalling their campaign.